You recognize the name, but shrug with indifference at its mention. In mint condition, their shotguns compare not to the finer side-by-sides of the past. They sell for pennies on the dollar relative to the spendy, yet (occasionally) affordable names like Fox and L.C. Smith, and may as well be a door prize for simply viewing a Parker. Although less glamorous, the single-shot Harrington and Richardson (H&R) shotgun may arguably be one of the simplest and most prominent firearms to grace American hunting and shooting history.

H&R boasts an ornate heritage dating back to the inception of the company in 1871 as Wesson and Herrington in Worcester, MA. Established by Gilbert H. Harrington and William A. Richardson, the manufacturer we know as H&R was not so named until 1877. Harrington supposedly bought out Dan Wesson’s investment and re-branded with Richardson, carrying the H&R name and parent operation through 1986. Their doors remained closed until 1991 when a new company started under the name H&R 1871.

H&R was known into the 1880s for their revolvers, but evolved quickly to manufacture shotguns and rifles with dozens of different models. But the name as I and many others have come to know is married to their single-shot shotguns.

In 1901, H&R produced their first single-shot, the Model 1900. A series of small-bore .410 single-shots followed, chambered in two-inch in 1911, the Model 1915 chambered in 2.5-inch, then a three-inch chambering in 1937. It appears the more commonly known “Topper” model name did not appear until the 1940s.

The H&R Topper Model 158 (Topper 158) was manufactured between approximately 1962 and 1973, becoming the shotgun many of today’s hunters associate with the H&R name. While this model was chambered in everything from .17 to .300 magnum caliber, smooth bores appear to be most common.

The Topper 158, like its predecessors, carried a hardwood stock, but the rubber butt pad didn’t appear before this model, according to vintage advertising. Their actions were color case hardened, boasting a beautiful tiger-like, almost holographic striping. Twelve, 16, 20 gauge and .410 bores were available with barrel length ranging from 28- to 36-inches and housing an immaculate shell ejector. The 28-inch barrel package weighed a scant 5.5 pounds. The forearms on early models were held tight to the barrel with a center screw, which was changed to a sleeker clip-in mechanism in 1971.

These guns may not have been dazzling, but their reputation as lightweight, reliable and affordable, led to hundreds of thousands of sales while in production. Original cost for a standard Topper shotgun was listed at $28.50 in 1957, and the Topper 158 at $36.95 in 1971, according to vintage advertising.

Present day value for a used Topper 158 in excellent conditions runs between $150-225, but monetary value does little justice for the antiquity of these “working class” scatterguns. But as W.E. (Bill) Goforth said in his in-depth volume on the H&R company, firearms enthusiasts are led to “…the belief that the value of a collectible firearm is measured by its cost.” This dismisses historical relevance, allowing monetary value alone to determine the “worth” of a firearm, exemplified by H&R.

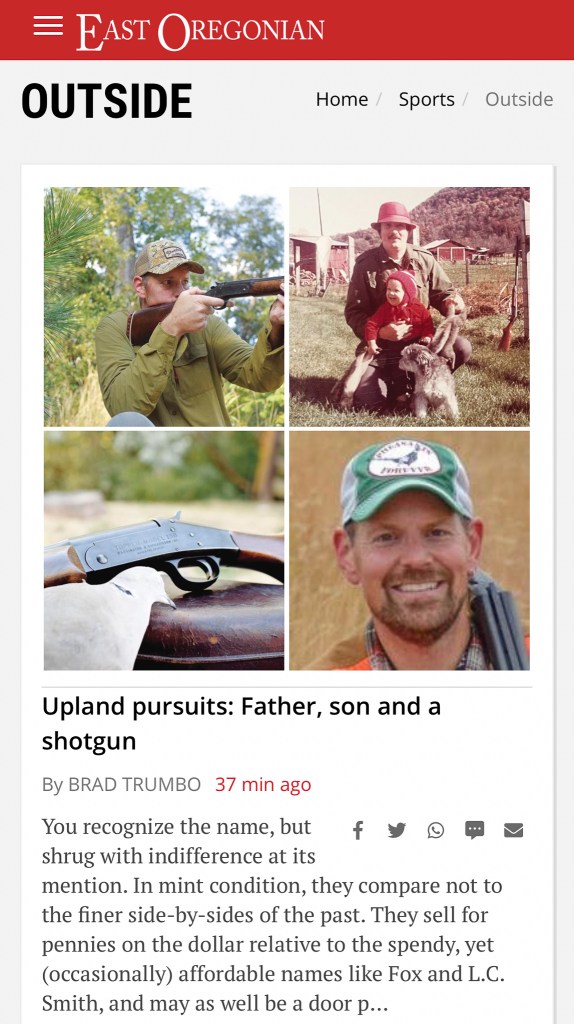

Aside from monetary or historical significance, sentimental value can eclipse all. I inherited my father’s Topper 158 as a child and carried it after gray squirrels through the deciduous forest. I recently discovered a photo of my father taken at his parent’s home around 1981. He knelt in the yard clutching his one-year-old youngest son (me) and a gray squirrel, the Topper 158 leaning against the fence in the background. The photo triggered a desire to rescue and restore the gun as a piece of my father’s legacy. A shotgun built for everyone and fitting of his humble, reliable personality.

A tiny Trumbo with his father after a successful squirrel hunt with the Topper 158

The christening of the old 12-bore with renewed fashion came a nation away from its Virginia origin with a passing shot at a Eurasian collared dove. A bird I doubt my father had ever heard of. Memories overlaid by time rushed to the surface, cued by the thump of the light-weight single-barrel driving against my shoulder.

With such talk of commonplace style and mechanics, it may be surprising that in 1880, H&R became the sole American licensee for the manufacture of quality English Anson & Deely double-barrel boxlock shotguns, manufacturing approximately 3,500 of various “grades” between 1882 and 1885. Not to belittle the company’s contribution to the U.S. armed forces over the years.

In November of 2000, the Marlin Firearms Company purchased the assets of H&R 1871, Inc. Presently marketing its products under the brand names of Harrington & Richardson® and New England Firearms®, H&R 1871 is currently the largest manufacturer of single shot shotguns and rifles in the world1. So why are single shot scatterguns so uncommonly seen afield? With a wealth of quality doubles and auto-loaders on the market, it seems hunters value the opportunity of additional rounds.

The H&R name and Topper 158 have claimed their worthy place in American firearms history and the story continues with current Topper models. Still produced under the Harrington and Richardson name, the Topper Deluxe Classic sports a vented sight rib, screw-in choke tubes and checkered American walnut stock.

Various vintage Topper 158 and youth models can be found around $100 if you are willing to watch auctions and make some minor repairs. Cheap enough to determine for yourself the wingshooting “worth” of H&Rs classic single-shot.

Getting the feel for a newly-restored classic.